In his essay “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,” film theorist André Bazin observed that image-making was “no longer a question of survival after death, but of a larger concept, the creation of an ideal world in the likeness of the real, with its own temporal destiny.” Under the lens of this 70-year old phrase, telescoped layers of meaning unroll panoramically from “Captains of the Dead Sea,” Alia Malley’s exhibition of Southwestern desert photographs that masquerade as aged snapshots from other planets and collectively imply a fabricated narrative of early space exploration.

We understand outer space primarily through images, which at best are spurious mediators whose fidelity may be further muddied by human conjecture and political motives. After all, conceptions propelling extraterrestrial investigations are necessarily geocentric. In this sense, extraterrestrial exploration and documentation thereof involve reaching for “an ideal world in the likeness of the real.” Malley’s exhibition reflects this notion while mining its epistemological dubiousness.

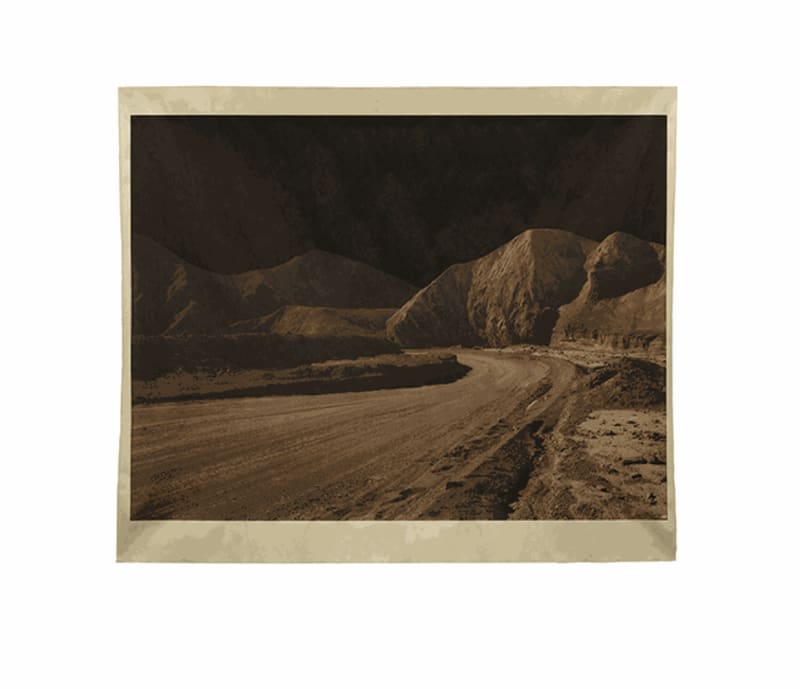

Shot in places like Death Valley and Arizona, her landscape photos convey the vast nothingness and confusing topography usually associated with scenes from outer space. In DV_8302 (2014), for instance, a whitish expanse that is probably a dry lake of alkali deposits looks as much like a swirling cloud on a Jovian planet. DV_8332 (2014/2015) could easily stand in for Mars terrain.

Other images more literally suggest space exploration clichés, like DV_7202 (2013/2015), which shows footprints in dirt. A few portray astronomical events as seen from Earth; LA_30154 (2013/2015) captures a moment from a transit of Venus.

Newsprint surfaces dull the images’ already muted colors, conferring upon them a timeworn appearance. Affectation of old newspaper clippings is furthered by the fact that each image is printed much smaller than its paper surface and is therefore surrounded by a wide frame of yellowish paper. DV_7276 (2013/2015) is divided in half, resembling a periodical spread.

Most of Malley’s photos are unique prints whose paper surfaces, even those framed behind glass, are not perfectly flat. Delicately rippled newsprint resonates the rugged topography, most notably in AZ_1140(2013/2015). The umbra of an outcropping in DV_8332 is echoed by a real shadow that the large sheet of newsprint casts on the gallery wall. These singular physical attributes heighten the photos’ artifactual appearances while insinuating that as 3D objects, Malley’s pictures parallel their depicted scenes even as they reference parallels between earth and other planets.

Likewise, Malley assumes the persona of a collector of newspaper clippings—or a fabricator of them, depending on the depth of one’s interpretation—whose nostalgic fantasies echo the wishful idealism implied by space exploration and its devotees. Launching rockets to places that few, if any, humans could ever visit indulges public curiosity and stimulates scientific research. The resulting images reveal little other than sparse emptiness while promoting folkloric mythologies about what could lie beyond our world.

Befitting an age in which concern for our own planet supplants curiosity about others, Malley’s photographs insist that Earth can be as intriguing as any other place—yet a better world always lies just around the corner.